Clint Eastwood is the rarest kind of writer-director: prolific. Stanley Kubrick, just two years Clint's elder, famously made Shelly Duval do so many takes on the set of "The Shining" she would break down in tears in the morning at the very thought of crying all day on Kubrick's repeated command. Eastwood, on the other hand, is famously an actor's director. He shoots scenes once, from the hip, calls cut, and gets out of dodge.

"I like to do whole sequences in one day ..." the director wrote in "Film Craft: Directing" (via Indiewire). "It's my job to make sure that the set and atmosphere ... are comfortable. That's the way to get the best out of people."

Eastwood has, as of this writing, 45 directorial efforts over six decades. That timespan and his huge catalog make his work hard to categorize but his one constant is his love of the craft. Here's the icon's best work behind the camera.

Play Misty For Me

"Play Misty For Me" is Clint Eastwood's 1971 directorial debut, and what's great about his opening gambit behind the camera is that it's nothing like the rest of his western-heavy canon.

Eastwood recalls getting his Director's Guild union card before shooting the film with immense fondness. "It was a great period in my life," he said in "Play it Again: A Look Back at Play Misty for Me," "and it was a very experimental time for me."

It certainty was. Eastwood plays a radio DJ and a bit of a lothario who gets a call every evening from a sultry-sounding woman requesting the same song. The film takes an unexpected turn into a psychological thriller, as the woman develops a kind of "Fatal Attraction" for the handsome radio personality. A young and perfectly cast Jessica Walter (of "Arrested Development" fame) plays the stalker. This is a film-nerd must-see, both as the director's nascent effort and as the one film where the western genre's most unflappable face goes from predator to prey.

White Hunter, Black Heart

"White Hunter, Black Heart" is adapted from a 1953 "what-if" novel of the same name loosely based on legendary director John Houston's making of "The African Queen."

Eastwood plays a version of Houston, "John Wilson," a brilliant yet troubled filmmaker running from his problems on his far-flung set. Wilson's film becomes a back-burner disaster as he begins fixating on hunting down an actual elephant in the room. "Houston wasn't above some sort of obsession," Eastwood said of the liberties they took with their subject's life.

Houston/Wilson, however, becomes conflicted over his desire to murder this charismatic and endangered exemplar of megafauna. Left-leaning Hollywood often thinks of Eastwood as a big conservative. He is big, and he did entertainingly talk to that empty chair at the 2012 RNC -- but part of Eastwood's conservatism involves actually conserving things, and here crafts a compelling psychological case study of found compassion for our animal friends.

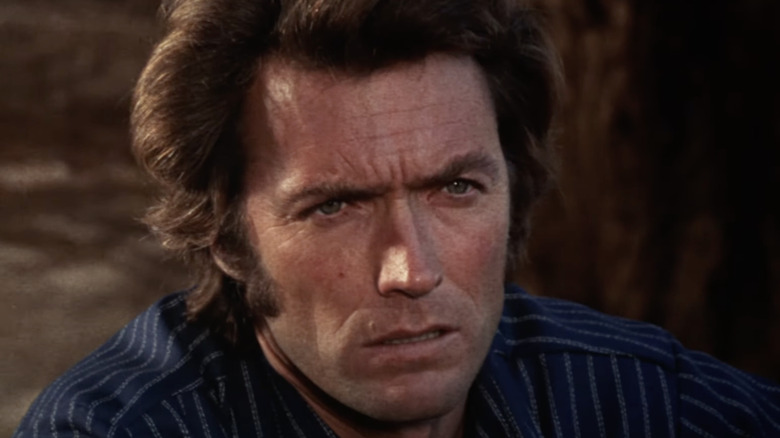

Sully

"Sully" was a unique challenge for Clint Eastwood. On a cold January day in 2009, Captain Sully Sullenberger, flying US Airways Flight 1549, lost both engines immediately after takeoff from New York and was forced to land in the middle of one of the most populated places on earth.

And land he did -- in the Hudson River, saving every soul on board. Sully was immediately hailed as a national hero. So what's the conflict here? And how do you turn 90 seconds of flying into a 90-minute movie?

Tom Hanks plays the ace pilot as exactly the kind of grey-haired elder-statesman of airline safety you always hope is in charge when you board a plane. The script focuses on the supposedly tense safety investigation that probed the pilot's dramatic judgment call. It feels thin considering the press dubbed Sully's spectacular landing the "miracle on the Hudson;" what makes the film work is the actual crash. Eastwood's simple staging (as opposed to, say, the frantic energy of Paul Greengrass's "United 93") lets this story of professional excellence unfold on the face of Hanks, at his reassuring best, and an air-traffic controller played by Patch Darragh. It's inspired stuff.

Richard Jewell

Clint Eastwood's chiseled scowl and 6'4" frame made him a natural acting alpha male in countless classic westerns. Given that gift, it's somewhat surprising what a touch he has for directing an underdog.

The real Richard Jewell was like bizarro Eastwood, short of six feet and "heavy set," says The New York Times. He was also a bit of a cop wannabe. That's how he ended up working security at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, where he discovered a homemade bomb and quickly evacuated civilians. The device went off, killing one woman and injuring 111. Jewel was a hero but local media soon branded him a suspect. The real bomber would be caught, but not before Jewell's life was destroyed. "He became the poster child for the wrongly accused," his attorney said. Jewell later won libel suits against CNN and NBC who had piled on the rush to judgment.

Jewell was also railroaded by the FBI, who used his eagerness against him. Eastwood's understated biopic portrays Jewell as a tragically naive mama's boy so desperate to become the kind of heroic lawman Eastwood so easily depicted that he repeatedly throws himself into the teeth of an obviously dishonest media and law enforcement conspiracy. "Richard Jewell" is about the mismatch between one simple-minded man's belief in a fable version of America, and the ruthless but obvious truth that lies beneath.

A Perfect World

In "A Perfect World," a prime Kevin Costner plays a charming convict who makes a Shawshank-style jailbreak but abducts a young boy in a moment of panic as he flees. Soon, a Texas Ranger is hot on his heels. When the camera pans from a fresh pair of cowboy boots kicked up on a cluttered desk to reveal Eastwood as that Ranger, the shiver down your spine simply means you've entered the intended atmosphere.

Or maybe not. Eastwood then oddly sidelines himself for the entirety of this 1993 film (set in 1963), badly mismanaging his otherwise interesting mid-career transition from cool to crotchety. He's useless as teats on a boar here, driving around aimlessly in an airstream trailer, bogged down in a dated gender-role standoff with Laura Dern, who plays some sort of equally extraneous criminal profiler. No law enforcement character accomplishes one bit of relevant police or plot work in the entire film.

That said, if you just mentally cut these superfluous scenes, "A Perfect World" has the ethereal free-wheeling fugitive feels of Terrence Malick's early work, like "Badlands." The tragic father-son bond Costner's paternalistic but dangerously unhinged fugitive forms with the resilient boy in his charge is the real draw, and very worth the stretch.

Flags Of Our Fathers

Clint Eastwood is just slightly too young to have served in World War II. He missed the defining moment of the "greatest generation" by only a few years, but he's plenty old enough to remember the conflict vividly. Quite obviously, he also recalls those who left as boys hardly older than himself and returned hardened warriors -- with the scars to prove it.

"Flags of our Fathers" tells the backstory of the American men on the brutal eastern front who were immortalized in the iconic photo of US Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima. The photo has long been rumored to have been staged, but multiple investigations showed it was authentic, according to National Geographic. However, the Pulitzer-winning pic was indeed rolled into the requisite war propaganda effort -- and so were the unwitting men captured in it. The film isn't flawless, but Eastwood tells this true story with the tenderness and regard these men earned.

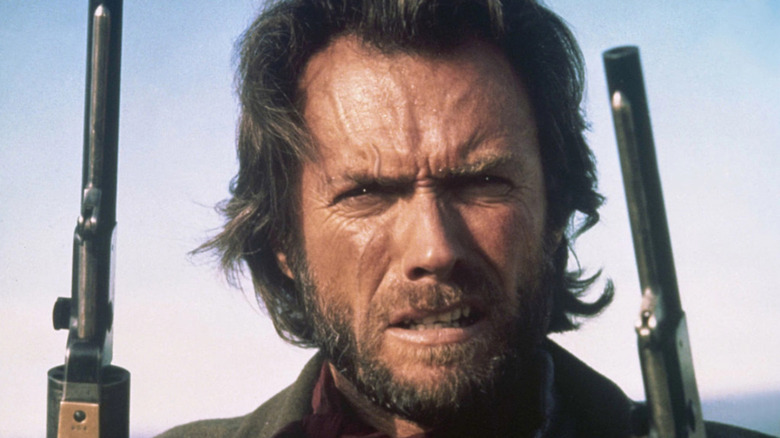

The Outlaw Josey Wales

It's unimaginable a film made today, one set at the tail end of the Civil War, would skirt the issue of slavery. It's clear "The Outlaw Josey Wales" would be against it, but in Clint Eastwood's imagination, the bloody conflict is a perfect backdrop of lawlessness that gives his eponymous anti-hero license to kill.

Here, the only reference to the practice is a clever rebuke via the women in the film's wild territories, who are often trafficked and at constant threat of rape. After saving a young Navajo girl, she pledges her life to Wales in her adopted Cherokee tongue. Wales can only reply, "You tell her I don't want no one belonging to me."

This is the radical equality of Eastwood's west. Wales is no white hat, playing a quick-draw ex-Confederate fleeing a gang of rogue Union war criminals who murdered his family. Along the way, Wales meets an elderly native man dispossessed of his land and still dressed like Lincoln for some ghastly government PR stunt. As the man shares his life-shattering story from the Trail of Tears, Wales, exhausted from his own exodus, literally falls asleep. Wales' frontier sense of justice means he treats everyone equally. Bore him with your problems and he will take the opportunity to nap. This film is a predecessor to Kevin Costner's later work, except Clint Eastwood doesn't dance. He shoots first and keeps it moving.

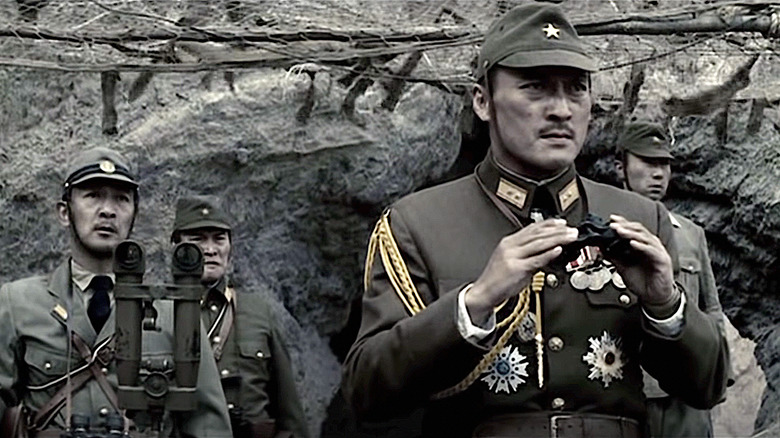

Letters From Iwo Jima

Imperial Japan committed countless atrocities during World War II as their forces were pushed into a rearguard defense of a crucial string of islands from Hawaii all the way to their own homeland. The zealous, cruel, and often suicidally brave fervor of this ancient honor culture made it hard for American warriors to forgive and forget.

And yet, Clint Eastwood wants to remind fans of the sometimes jingoistic WWII genre of the humanity of those same fearsome forces. The eastern theatre was, initially, a close-run fight, but "Letters from Iwo Jima" takes you inside the doomed, late-war Japanese perspective of 1945. The once terrifying axis power is a shell of itself, living out Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto's apocryphal warning after their unprovoked attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. "I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve."

Ken Watanabe is devastating as a Japanese general who holds out for 36 bloody days as his forces are whittled down from 21,000 to just above 200. "Letter's from Iwo Jima" reckons with the tragedy of individual souls caught helplessly on the wrong end of this unfathomable global death machine.

Pale Rider

All westerns are in some sense Christian – in the broad sense that Christendom's sweeping incursion through a "new world" created the genre's inciting incident. This newly spoiled garden becomes the contested stage where the fall of man is played out all over again.

"Pale Rider," however, might be the only explicitly Christian western you could safely recommend to both a faithful flock and your more average blood-thirsty genre-loving heathen.

Clint Eastwood stars as a mysterious drifter – but the only thing this avenging angel is hiding under his duster is the clerical collar of a man of God. Eastwood's "preacher" has no actual Christian name to credit, a familiar (and this time ironic) trope of Eastwood westerns. "Preacher" first emerges from the mountain mist as a literal answer to a frightened girl's prayers to protect her family from a sinister mining operation set to steal their land, and worse. In Eastwood's three great westerns as a director, he plays, respectively, God in "Pale Rider," Lucifer in "High Plains Drifter," and then the fall of mankind itself in "Unforgiven." The guy has range.

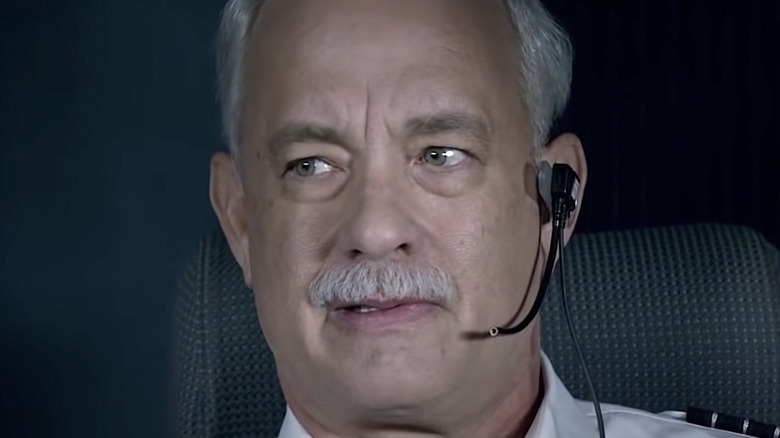

High Plains Drifter

In Clint Eastwood's most savage portrayal of a wild west gunslinger, "High Plans Drifter," the director plays another nameless cowboy who rides directly into one of those familiar dusty towns made mostly of sawhorse planks and pinewood frames. The imminent return of a brutal gang forces the townspeople to enlist Eastwood as a protector, and protect them he does -- but at great expense.

The most jarring thing about this 1973 film is Eastwood also casts himself as a rapist. When a young woman who wants the attention of the new tough guy in town slaps the cigar out of Eastwood's mouth, "The Stranger" (as he's credited) drags her into a barn in "broad daylight" and assaults her. When he's done, an incongruously triumphant shot is positioned between Eastwood's legs as the ravaged girl lay on a pile of hay with the brutal cowboy looming over his conquest.

Eastwood is still broadly embodying the laconic gunslinger of Sergio Leone's spaghetti westerns, but with a more biblical view of the era. This town is so beyond any law it becomes a blatant metaphor for Hell, returned to a feudal state in which a king is just the devil best equipped to use their dark triad traits cleverly.

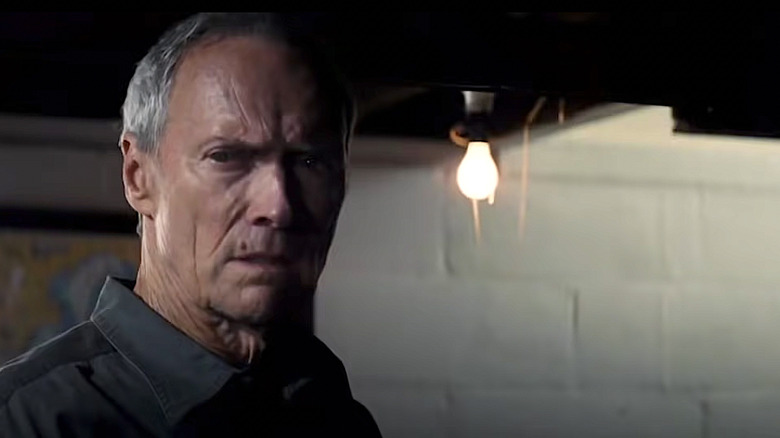

Gran Torino

"Gran Torino" was a bit of a surprise hit in 2008, pulling in nearly $270 million on the film's modest $33 million budget. That monstrous return may be why Clint Eastwood is still able to finance adventure films starring himself even in his 90s, like 2021's "Cry Macho."

In "Gran Torino," Clint plays another lovable "get off my lawn" grouch: a Korean War vet dismayed his suburban Michigan neighborhood is being resettled by Asian immigrants. Foreign gangs are also taking over this once-thriving center of All-American industry, but Eastwood's Walt Kowalski forms an unlikely bond with a neighborhood Hmong boy that upends his prejudice and kicks off one last heroic stand for the former military man.

Late-career Eastwood is at his best as the reluctant mentor. He also brilliantly leans on his own Hollywood mythos to pack an emotional punch into the ending that no other artist could similarly summon. Eastwood of this era repeatedly pulls his hard-boiled image off the stove to throw onto an anti-hero conflagration. "Gran Torino" is his second-best of these efforts. His best, of course, is somewhere below.

Mystic River

Every good world-weary detective eventually grapples with the futility of it all. In David Fincher's iconic "Se7en," Morgan Freeman's Detective Somerset describes his procedural curation of horrors as "picking up diamonds on a deserted island, saving them in case we get rescued."

Clint Eastwood's "Mystic River" is not as dark, but it's the director's most somber and elegant work. Sean Penn plays a grieving father and small-time gangster in a tight-knit Boston neighborhood. When his daughter is brutally murdered, the investigation takes a shocking focus on one of his childhood best friends, played by Tim Robbins. Kevin Bacon plays another grown-up kid from the old neighborhood, now mediating between the two men, serving as the cop in charge of the investigation.

Bacon's detective has lost faith, too, saying: "Sending killers to jail is just sending them home to the place they've been headed all their dumb, pathetic lives. The dead are still dead." Eastwood constantly cuts to aerial shots of the Charles River running through Boston. The river is mystical because this is a film about fate. As tensions escalate, everyone seems to know the smallest thing could've changed the tragic flow of this tale. And yet, no one has the power to swim to shore.

Million Dollar Baby

If Clint Eastwood had finished his filmmaking career and never touched the sweet science, it would've been a tragedy. Eastwood clearly has a love of boxing, but he's too inquisitive to remake "Rocky" or "Raging Bull." "Million Dollar Baby" has plenty of action, but it's not carried by pugilistic masochists enduring beautifully shot brain damage.

"Million Dollar Baby" swept the Oscars in 2005, including two statues for Eastwood. The subtle script is perfectly accented with a scant, finger-plucked score Eastwood largely composed himself. The director's minimalist approach again works wonders and is part of what makes this film so timeless.

Here, Eastwood plays a gruff boxing trainer who reluctantly turns Hillary Swank's old but heavy-handed novice into a champion -- before cornering her through something much grimmer. "Million Dollar Baby" is devastating, and perhaps the most beautiful film ever made about the deep, platonic love that can exist between a coach and his prized protégé.

American Sniper

The critical reaction to Clint Eastwood's "American Sniper" was suspect of such an openly patriotic film. Rolling Stone called it "almost too dumb to criticize" and a "well-lit little fairy tale with the nutritional value of a fortune cookie." The New York Times, meanwhile, buried it for "turning complicated historical events and characters into fables and heroes."

Not a warm welcome from the professional filmgoing set! Actual ticket buyers, however, loved this drama. "American Sniper" was Eastwood's biggest hit, raking in well over half a billion box-office dollars, says ET Canada.

"American Sniper" is the largely true tale of the real-life Navy SEAL Chris Kyle, the "deadliest sniper in American History." The film makes much of his nickname, "The Legend," maybe because Kyle was turned into one in 2013 when he was murdered on the home-front by a fellow soldier. Before his death, the real Chris wrote the book on his own mythology, started telling wild stories about gunning down bad guys on American soil, and allegedly exaggerated his military valor by puffing up his medal count. Eastwood's tribute, however, is about the part of the warrior's life that is undisputed. Kyle served bravely in America's modern wars, and the unique trauma of those conflicts scarred his mind and took his life, too.

Unforgiven

"Unforgiven" isn't just Clint Eastwood's best film -- it's the best western ever put to film, period, and one of the greatest pieces of movemaking ever undertaken. But the stature of the film has nothing to do with Eastwood's Oscar win for best director, or its place atop countless listicles, this one included.

Enjoying "Unforgiven" is easy -- it's a cracking western even if you spend half the film on your phone (Don't do that). What makes this masterpiece fascinating takes some context about the western genre, and an understanding of Eastwood himself.

"Unforgiven" is the ultimate "anti-western," a genre that attempts to deconstruct the tropes of the classic cowboy melodramas in which good guys in light hats outdraw bad guys in dark ones. The film has a lot to say about shootouts in particular. "Unforgiven" proposes an intuitive take on what kind of sand actually steadies the hand of a man known to win a gunfight. Hint: it's not a quickdraw contest. Gene Hackman is genius as a ruthless sheriff hell-bent on gunning down these cliches, too. But it's really Eastwood as the film's lead who, at age 61, relies on the audience's familiarity with the fearsome characters he played in his youth to convey the truth about human frailty, western fables, and luck of the draw.

Read this next: The 20 Best Westerns Of All Time

The post The 15 Best Clint Eastwood-directed Movies, Ranked appeared first on /Film.